Lessons for libertarians on how to win the battle of ideas.

Upon discovering the freedom philosophy, many people feel as though they have discovered the solution to society’s problems. And indeed, they have discovered a critical part of it, namely, the rules and social institutions that will lead to human flourishing.

But simply possessing these ideas can’t be the totality of the solution. If it were, we would have already solved the problem.

As it turns out, there’s a second problem we need to solve if we are to achieve freedom and prosperity, and this is the problem of persuading the masses. As Mises wrote in Human Action, “The flowering of human society depends on two factors: the intellectual power of outstanding men to conceive sound social and economic theories, and the ability of these or other men to make these ideologies palatable to the majority.” The first factor has been essentially satisfied. The second is the one we are stuck on.

In light of this, creating a free and prosperous world is not really an economics or philosophy problem at this point. It’s a psychology problem. To change the world, the libertarian must have a firm grasp not only of the rules and institutions of a free society, but also of the art of changing people’s minds. In short, he must be a student of persuasion.

One good place to begin this study is the aptly named book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, written by Robert Cialdini in 1984. In this famous book, Cialdini outlines six key principles of persuasion. They have been summarised as follows:

- Reciprocity: When we receive something, we feel obliged to give something back.

- Consistency: We feel compelled to be consistent with what we’ve said/done in the past.

- Social proof: When we’re uncertain how to behave or react, we look to others for answers.

- Liking: We’re more likely to agree to someone’s request if we know and like him/her.

- Authority: We tend to obey figures of authority (people with titles or expertise).

- Scarcity: We perceive something to be more valuable when it’s less available.

Knowledge and Character

Though all six of these principles would be valuable to study and apply, two of them in particular stand out: Authority and Liking. They are noteworthy because they seem to be 1) relatively easy to implement in a wide variety of contexts, and 2) very impactful when implemented.

One way of implementing the Authority principle is to make an impression with titles and aesthetics. But the real power comes when you just are a genuine authority. When you really know what you’re talking about, people listen. When you have genuine mastery and expertise, people will be far more willing to hear you out and change their minds based on your ideas. As Robert Heinlein said, “your best weapon is between your ears and under your scalp—provided it’s loaded.”

The practical takeaway is this: To change the world, we must be good at persuading. To be good at persuading, we must, among other things, be intellectual authorities. To be authorities, we must know our stuff. And to know our stuff, we need to crack open some books and get reading. And I don’t just mean reading the basics. We need to be familiar with every political philosophy out there. We need to have answers to every argument. We need to be autodidacts, erudites, polymaths, the most well-read person in the room, no matter the room.

That’s incredibly hard to accomplish, of course, but imagine the persuasive power of such a person. No matter how crazy your ideas are, people would feel compelled to take them seriously.

The other standout principle is Liking. Now, anyone can be decent, but again, that’s not enough. If we really want to be persuasive, we need to be the most likable person in the room. We should be known for our approachability, our easygoing attitude, our sense of humour, our charm, wit, laughter, warmth, exuberance, maturity, and congeniality. We don’t have to be the life of the party. But we do have to be the kind of person other people like being around.

The shorthand I’ve developed for these two principles is knowledge and character. If we just dedicate ourselves to working on those two things, I’m convinced we would all be 10 times as effective at persuasion, and thus at changing the world for the better.

One of the most high-profile examples of these principles working is the political conversion of Dave Rubin. As you may know, Dave Rubin was a leftist who became a libertarian roughly six years ago after talking with some big names on the right and being persuaded by their arguments. What you might not know, however, is why exactly he found these individuals so persuasive.

Here’s how he told the story in an interview last October.

“As far as my wake up, there were a couple moments, the most famous one which now I think has been seen probably about 50 million times on YouTube is when I had Larry Elder on (in January 2016). Larry Elder is a black conservative, really a libertarian, but this was about five years ago and I was still a lefty. We got into it about systemic racism and he just basically beat me senseless with facts. And instead of doing what most lefties do, which is call him a horrible name or cancel the show or kick him out or whatever, we aired it, we aired it as is, and a few days later I saw a lot of people in the comments going, ‘you know, Dave kind of listened.’ And I did kind of listen, and from there I started talking to other people, say Dennis Prager, Glenn Beck, Ben Shapiro, the list goes on and on, and I started finding that although I had some disagreements with some of these people on the right - and I still do by the way - that they were very open to discussing them, they knew what they thought and why they thought it, and I found them honestly - this was the most shocking part - I found them nicer. That really was the real shocking part. Because there’s this meme that somehow on the left, the left must love tolerance. So, the implication is that the people on the right are bigots and angry. And it just simply is not true. Since I have gone through this metamorphosis, transition, whatever you want to call it—and now I hang out with all these scary right-wingers, they are happier, they are more generous of spirit, they smile more, they laugh more, and most importantly, they’re willing to agree to disagree.”

Did you catch that? “He just basically beat me senseless with facts.” “They knew what they thought and why they thought it.” “I found them nicer.” “They are happier, they are more generous of spirit, they smile more, they laugh more.”

What did Larry Elder and the others have that made them persuasive? They knew their stuff inside out and backwards and they were fun to be around. They had knowledge and they had character. And look how much Dave Rubin has done for the cause of liberty, all because a few individuals did their homework and learned to be likable.

Libertarian Victory Is a Self-Improvement Problem

Leonard Read—the guy who founded FEE and wrote I, Pencil—stressed these two themes throughout his writing. On the knowledge point, consider this section from his 1962 book Elements of Libertarian Leadership.

“There are millions in America today who are taking firm ideological positions, some on the side of governmental and labor union control and dictation, others on the side of freedom to produce, to exchange, to live creatively as each chooses. But observe the small number on either side who can do more than assert their position. Only a few can explain with reason and clarity why they believe as they do. This may be consistent behaviour for the coercionists, but there is no reason why those of us who believe in freedom should follow their pattern. We do not need to impugn the motives of those who have not as yet grasped the significance of freedom nor do we need vociferously to argue for points we cannot explain. Quite to the contrary, we can turn conscientiously to our own homework; we can aim at becoming competent expositors.”

Character was also of central importance to Read. In his view, the liberty movement doesn’t need more people so much as it needs better people. Here’s how he put it in his 1973 book Who’s Listening?.

“The trend is away from liberty; the problem is how to reverse direction. How shall we go about this task? Do we need to rouse the masses? No, ours is not a numbers problem. There are tens of thousands, perhaps millions of persons—more than the job requires—who frown on all forms of authoritarian collectivism and who favour liberty. The failure of this multitude to generate a trend toward liberty lies in inept methods; indeed, most of us, by our lack of proper posture, aggravate rather than alleviate our social woes. Unwittingly, the would-be friends of liberty aid its foes…

…As a starter, take stock of all the antisocialist, pro-freedom individuals of your acquaintance. How many can you find who are not angry—who are not name-callers? True, some express their spite in elegant prose; but spite is spite regardless of the verbal dress it wears. Do you not find that the vast majority are out of temper? Embittered warriors? Intolerance, confrontation, disgust with those of opposed views engender not improvement in others but resentment, not progress but regress. This, I insist, is a mood that does more harm than good; dead silence would be preferable.”

To Change the World, Change Yourself

Changing the world is possible, but the reason most people don’t do it is because, frankly, they aren’t willing to put in the work. They aren’t willing to read 50 books a year. They aren’t interested in going through the painful process of acknowledging and correcting their character flaws.

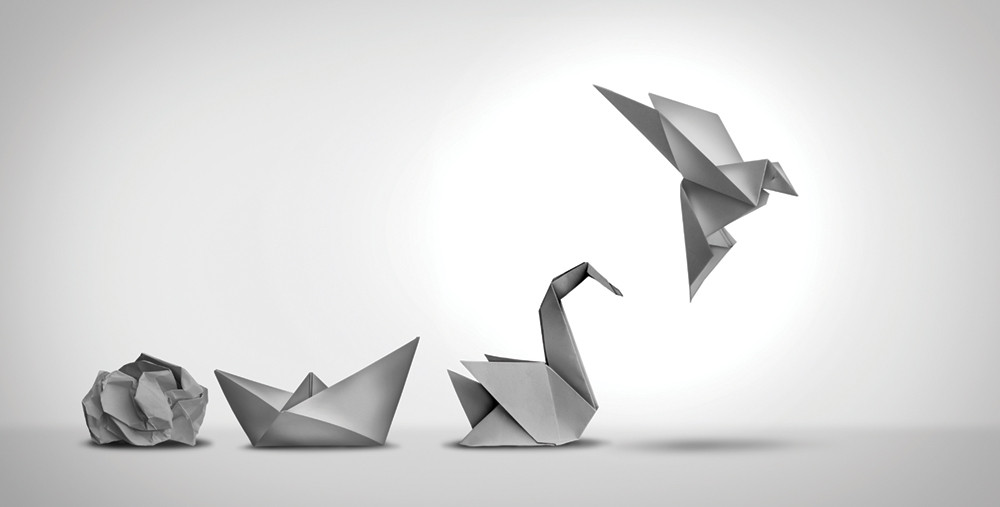

But if you’re willing to do that, if you’re willing to throw everything you have at improving your knowledge and character, there are very few limits to what you can accomplish. Dave Rubin’s political conversion is a testament to this approach. And FEE’s legacy of bringing thousands into the liberty movement is also a testament to this approach. Most people are not all that interested in changing the world when they realise that doing so requires a hefty load of homework and personal growth. But there are a few who dare to try. And it is those few who make all the difference. ![]()

Source: fee.org