Recurring incidents of cooperative fraud in the country have raised serious concerns about the regulatory institution’s capacity to protect depositor funds. Although cooperatives are traditionally regarded as having strong internal controls and self-regulation, due to their member-based structure, recent events have uncovered a different reality. Investigative reports have exposed fraudulent audit reports, fictitious borrowers and shareholders, and rampant embezzlement of funds within cooperatives, revealing the depth of the sector's vulnerabilities.

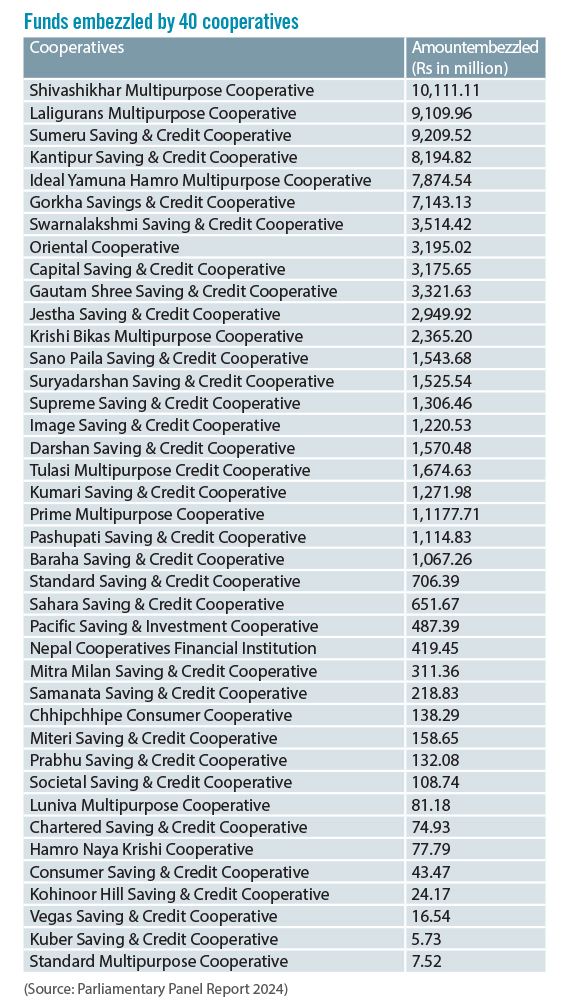

The recently formed Parliamentary Committee tasked with examining the misuse of cooperative deposits has uncovered alarming findings, estimating that Rs 87 billion has been embezzled by promoters and high-level management within cooperatives. The report, presented to parliament, was based on a study of 40 major cooperatives, including 22 identified as problematic. However, due to systemic weaknesses in governance, internal controls and the effectiveness of oversight, it is estimated that deposits totalling Rs 250 billion remain at risk. The government has yet to devise a concrete strategy to address this significant financial scandal or to safeguard the interests of depositors adequately.

Political protection has enabled many perpetrators to escape accountability. According to Surya Bahadur Thapa, Chair of the Committee on Cooperative Embezzlement, certain individuals have evaded justice with the aid of undue political patronage.

Cooperatives as Ponzi schemes

Many cooperatives, particularly savings and credit cooperatives, operate in a manner similar to Ponzi schemes. They attract members with promises of high returns on deposits, essentially using the funds from new members to pay out to existing ones, creating what resembles a ‘paisa double’ offer. Eventually, when the pool of new members dries up, these schemes collapse, leaving depositors in financial ruin. The collapse of numerous cooperatives has had wide-ranging socio-economic impacts. So far, 22 cooperatives have been declared problematic by the government, with most of them being savings and credit cooperatives, alongside a few multipurpose cooperatives.

Deependra Bahadur Kshetry, former Vice Chairperson of National Planning Commission and former Governor of Nepal Rastra Bank, has called this a failure of cooperative laws, policies and regulatory institutions, attributing the scams to weak enforcement and oversight. He emphasises that the state should not ignore the plight of small depositors who have lost their life savings in these scams. Kshetry also advocates that cooperatives should be limited to the production and marketing of goods and prohibited from operating like banks and financial institutions (BFIs).

Currently, there are around 31,450 cooperatives operating across Nepal with a membership base of over 7.3 million people. Reportedly, they have mobilised over Rs 500 billion in deposits with nearly 14,000 of these cooperatives dedicated to savings and credit, authorised to collect deposits and lend to members. According to the National Living Standard Survey (NLSS) 2022/23, around 18.3% of Nepal's population relies on cooperatives for credit. However, contrary to their mandate to lend solely to members, cooperatives are extending loans in highly profitable sectors, which has contributed to asset bubbles, especially in real estate, housing and the automobile sector. Some cooperatives, such as Kohinoor Hill Savings & Credit and Vegas Savings & Credit collected vast amounts of money through advance bookings in housing projects that ultimately failed, plunging depositors into severe financial distress.

Political connections

The link between wealth and political influence has played a significant role in the cooperative crisis. The cooperative sector, prone to over-politicization, has been used by some individuals to leverage political connections. In contrast to banks and financial institutions regulated by Nepal Rastra Bank, which follow stringent guidelines under the Money Laundering Prevention Act, cooperatives have become a haven for unregulated, shadow funds. Unlike BFIs, which have capped cash transactions at one million rupees, cooperatives operate with minimal restrictions, often circumventing financial regulations and indulging in high-risk activities.

This exploitation of loopholes has been enabled by promoters who maintain close ties with politicians. For instance, figures like Ichchha Raj Tamang, a former member of parliament, and KB Upreti, former Cooperative Department Secretary of CPN-UML, are implicated in frauds involving Rs 7 billion and Rs 8 billion, respectively. Other promoters, such as CB Lama of Kantipur Multipurpose Savings & Credit and Surendra Bhandari of Laligurans Cooperative, have been taken into custody due to their evident involvement in fraud and are reportedly associated with the Nepali Congress. Chairperson of Rastriya Swatantra Party is under police investigation concerning his alleged role in cooperative fraud. Cooperative scams have now become part of public discourse and interest and its resolution is now a key topic in national discourse.

Weak regulatory and supervisory systems

The massive cooperative fraud stems largely from weak regulatory oversight, inadequate supervision and undue political patronage of promoters. This negligence by state mechanisms has left many low-income individuals and small business operators vulnerable. The lack of effective regulation and supervision by responsible bodies such as the Ministry of Land Management, Cooperatives and Poverty Alleviation, and the Department of Cooperatives, has prevented the identification and management of systemic risks. While the department oversees 125 large cooperatives, provincial registrars handle nearly 6,000 cooperatives, and local levels oversee 23,759 cooperatives – representing 80% of all cooperatives. However, local governments lack the capacity and human resources to fulfil this regulatory responsibility. Adding to this problem, provincial cooperative registrars can issue licences without local-level consent, creating further inconsistencies in regulation.

Meanwhile, organisations intended to support cooperatives such as the National Cooperative Federation of Nepal and various Provincial and District Cooperative Unions operate as cooperatives themselves, in conflict with legal standards. Despite this contradiction, regulatory bodies have yet to take corrective action.

How safe are BFIs

In the wake of cooperative fraud, public trust in financial institutions has wavered, with many wondering whether their deposits in BFIs are secure. Nepal Rastra Bank has assured depositors of the safety of their funds with NRB Governor, Maha Prasad Adhikari, asserting that as the custodian of depositor funds, the central bank enforces strict adherence to regulatory norms. Deposits of up to Rs 500,000 are insured, and the central bank plans to increase this amount over time to further protect small depositors and reinforce trust in BFIs.

Sunil KC, CEO of NMB Bank and President of Nepal Bankers’ Association (NBA), has repeatedly assured that Nepal's banking sector operates under prudent governance, closely regulated by the central bank.

Governor Adhikari has also called for a comprehensive overhaul of the cooperative sector, emphasising the need for a second-tier regulatory institution dedicated to cooperative oversight. He noted that many cooperatives lack reliable balance sheets, highlighting the need for investigations to trace the movement of cooperative funds. The parliamentary panel's report further indicates that some promoters have moved funds to foreign countries, underscoring the importance of stronger regulatory action.

Some relief, yet a lot more remains to be done

Amid this crisis, the Office of the problematic Cooperative Management Committee has returned deposits to 6,155 individuals by managing assets, selling properties, and recovering loans from troubled cooperatives. In total, Rs 1.48 billion has been reimbursed to depositors affected by problematic cooperatives, according to Minister for Land Management, Cooperatives and Poverty Alleviation, Balaram Adhikari. Additionally, under partial settlement terms, 438 depositors have received Rs 30 million till date, with funds deposited directly into their bank accounts.

Despite these efforts, a large number of depositors continue to protest, demanding the prompt return of their savings. Victims urge the government to expedite settlements by managing and selling assets, recovering loans and implementing other measures to ensure their deposits are reimbursed in a timely manner. They argue that penalties for promoters involved in fraud are insufficient and that swift action to return depositors' money is paramount.

-1765706286.jpg)

-1765699753.jpg)