Proponents of tariffs often say “free trade” is impossible because other countries would never agree to it, but that view misses the point.

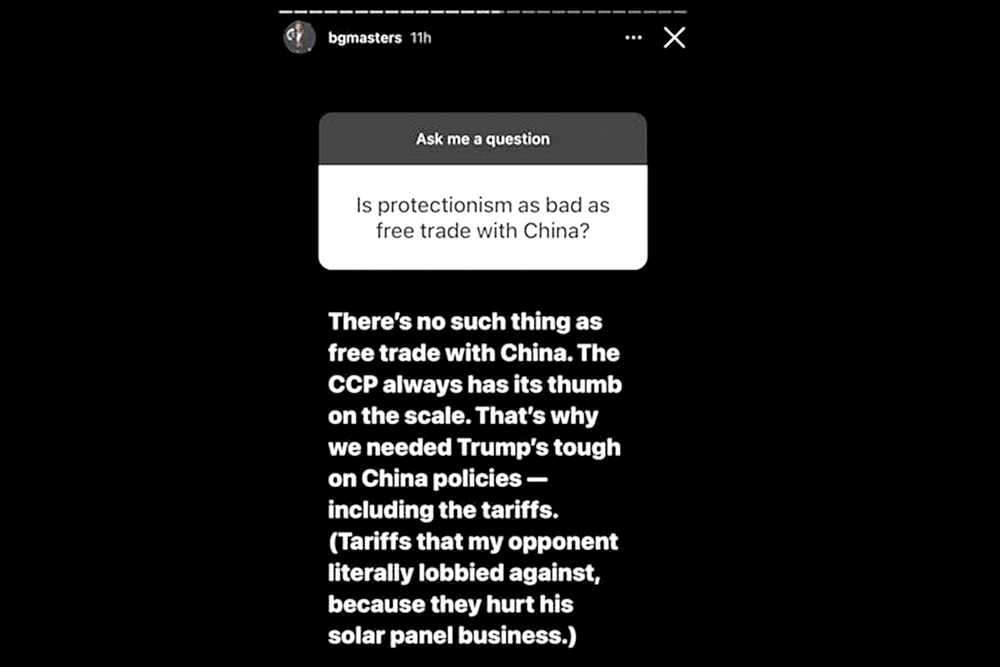

“Free traders are trapped in a public policy version of Groundhog Day,” Julian Sanchez wrote in 2003, “forced to refute the same fallacious arguments over and over again, decade after decade.” It’s been almost another decade since then, and Sanchez’s point is just as relevant. Blake Masters, a Trump-endorsed businessman who’s now running for the US Senate in Arizona, recently held a Q&A session on his Instagram page where he announced his support for tariffs on Chinese goods. He follows the Trump Administration’s reasoning that the Chinese government’s interventions, like subsidies for some exporters, give their products an unfair advantage over American goods in international trade. The only sensible policy for America, they say, is to hit back with tariffs of its own. The idea of tit-for-tat tariffs goes back at least to Thomas Jefferson in American politics. But when Masters claims that “free trade” can’t even exist unless nobody intervenes in their trade policies at all, he misses how economists never let tariffs in some countries change their support for getting rid of trade restrictions at home. Free trade doesn’t need total freedom to still be a good idea.Make Trade Easier, Not Harder

Adam Smith, whose 1776 book The Wealth of Nations is considered one of the most important attacks on protectionism ever written, was perfectly aware that a world with total free trade could only ever be a “utopia.” And yet to Smith, a country that stops itself from trading with others “would obstruct instead of promote the progress of their country towards real wealth and greatness.” Contra Masters, Smith did not see any economic reason for tariffs in the realistic case for free trade. One reason why, as economic journalist Frédéric Bastiat would put it years after Smith, is because “reciprocal obstacles could only be reciprocally hurtful.” Trade is a two-way street, after all. If you make it harder for people to buy your product, you’ll also have a harder time selling it. Modern economists like Leland Yeager have also tried to drive home the idea that “foreign trade barriers deprive foreigners and us alike of potential gains from trade, just as our own barriers do.” The best thing to do is to lower those barriers as much as we can, not raise them even higher.Trade is a two-way street. If you make it harder for people to buy your product, you’ll also have a harder time selling it.Saying that economists mostly agree on anything can be very dangerous, but it isn’t an exaggeration to say that they mostly support the freedom to trade regardless of other countries’ tariffs. Economist Don Boudreaux is even willing to put his own money on it. And Paul Krugman, who won the Nobel Prize for his work in trade theory, goes so far as to say that “the economist’s” case for free trade is about no domestic tariffs, no matter what. When Masters claims that free trade with China is an impossible dream, he misunderstands what it means - and has always meant - to be a free trader.

How “Free Trade” Misleads

Why have trade economists had to make the same exact argument over and over again, year after year? I suspect that one overlooked reason (among many others) is because the rhetoric they use puts them at a disadvantage right from the get-go, and it comes down to the phrase “free trade.” The two sides often find themselves arguing about two very different things. As economic historian Deirdre McCloskey stresses, the way people say things matters a lot. For example, she believes that calling the West’s economic system “capitalism” tricks people into thinking that getting more capital is what drives the economy forward, while it should really be innovative ideas that get most of the attention. But why stop at just critiquing one word if there are rhetorical problems hiding in others? Masters’ argument about free trade reveals that the same misstep is happening in the trade debate, too. If you haven’t read the classics from Smith and Bastiat, it makes sense to believe that supporting “free trade” only means supporting a completely open world economy; that’s exactly what those words mean. “Trade” means that there’s more than one party involved, since you can’t exchange something with yourself. So, if we call trade “free,” then we imply that all the traders should be completely free of any government meddling. The average economist would agree that that’s the end goal, even if they know we’ll never get there. But if they only argued for that sort of free trade, then Masters’ idea that free trade with communist China can’t exist would be a very good point. Economists actually argue for “freer-than-it-otherwise-would-be” trade, which doesn’t have the oomph it needs to justify taking up space in newspapers and debates. Neither does the usual substitute, “unilateral free trade.” But if free traders want to stop repeating themselves to people like Masters, then it’s time to be clearer about what they mean when they argue for “free trade.” The answer might be as simple as calling it the “freedom to trade” instead, which puts the emphasis more on letting people make their own choices about what they buy. Those choices might not come from free governments abroad, but citizens are still allowed to make them if they’d like. That’s what it really means to support “free trade.” No matter what the best term might be, the stakes here aren’t just semantics. They could be peoples’ livelihoods. If somebody in office (like Blake Masters) comes across the well-researched idea that free trade helps lift the poor out of poverty, and thinks that “free trade” only means trade that’s equally free on all sides, then they’ll probably have a much different policy prescription than the economists who studied the issue. Like Masters and Trump, they might try to “balance” trade with more tariffs, making it equally unfree for everyone. Today’s free traders are the latest debaters in a rich tradition, and they won’t be the last to argue for it. But by changing the rhetoric they use; they might just give those who come after them an easier time convincing everyone of a simple truth: letting people choose for themselves is a good thing. Source: fee.org READ ALSO:

Published Date: July 27, 2022, 12:00 am

Post Comment

E-Magazine

RELATED Economics

-1758107444.jpg)