Text by Ujeena Rana

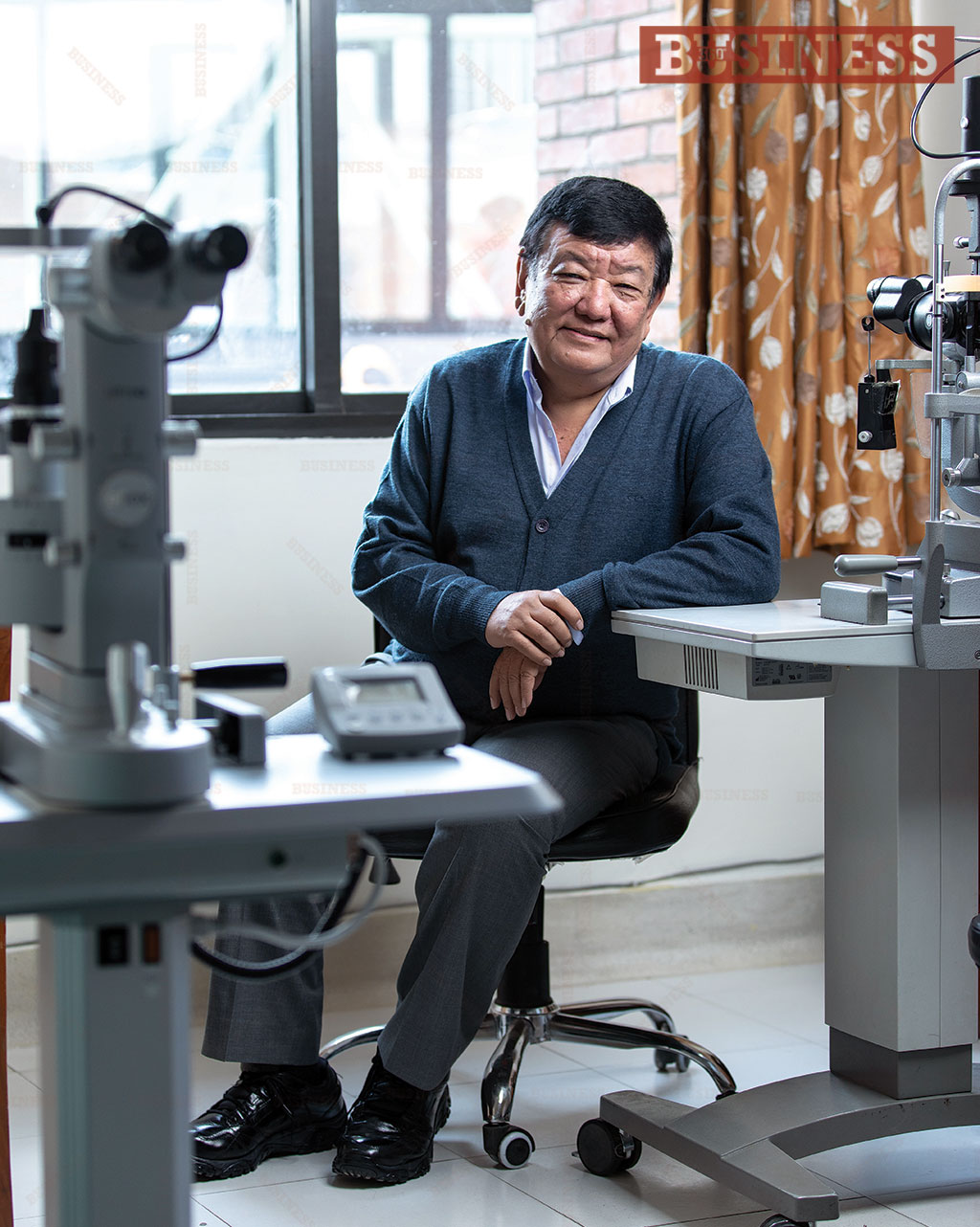

He has been called the God of Sight having served millions of people dispelling darkness and finding solutions to eye problems. He is celebrated in Nepal and overseas for his commitment and innovation to restoring sight. Dr. Sanduk Ruit is the recipient of the Prime Minister National Talent Award 2019. He received the Padma Shri Award on the occasion of the 69th Republic Day of India. He has been honoured with the Asia Society 2016 Asia Game Changer Award, Social Entrepreneur of the Year Award 2014 by Schwab Foundation, the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award in 2006 and the “Asian of the Year” title by Reader’s Digest in 2008.

Early Years

It was unconventional for parents in Olangchung Gola in the remote far Eastern Himalayan region where Dr. Ruit was born in 1955 to send their children to school. But what is even more astounding is that his father sent him to a school in Darjeeling. “It was his vision and I was able to attend a school at all. I consider that as one of the first steps to getting to where I am today,” comments Dr. Ruit.

The five years that he spent in Darjeeling was filled with cultural surprises in the beginning. He was forced to become somewhat a loner. Other students had their parents visit them and they went home on long holidays but he had no family visits and no one to share his loneliness with. He felt isolated. The school principal Father Mickey graciously looked after him.

Dr. Ruit discloses that two things transpired during this time: “Firstly, the experience really hardened me. I was a child between the age of 7-10 years, wanting to go back home and enjoy celebrations with family. I was away from that. In retrospection, it probably became a positive thing for me. My whole system and the way I approached life got a new outlook. It toughened me and it made me strong to face life. The impression I got from life was that I had to work and struggle three times more than other children. Secondly, spending time with Father Mickey during the holidays was very good because he used to give me a broad picture of life and he instilled good values in me.”

Finding Purpose In Tragedy

Dr. Ruit, however, could not complete his education in Darjeeling because of the ongoing Sino-Indian war. Schools were closed. Resultantly, his father brought him to Kathmandu and admitted him at Siddhartha Banasthali School. “My younger sister came in tow. Two of us were in Kathmandu, again a totally new place for us. Then suddenly, my sister started to get a cough and began losing weight. She was diagnosed with tuberculosis and put for treatment. After six months, she started responding well but in 9-10 months, she started getting sick again. We consulted a chest physician and were told that she was resisting the primary line of medicines. Those days, medicines weren’t very good. She needed a recently available second line of medicine which was very expensive. We could not afford it. Also, the medicine was not readily available in Nepal. After sometime, we took her home.”

By then the Ruits had shifted from Olanchuk Gola to Hile, Dhankuta where his father ran a small cloth store. A landslide had washed away their ancestral home.

“In Kathmandu, my sister and I had become closer. I had grown very fond of her. We had become friends,” he narrates. “As I saw her getting bad to worse and the cycle repeated, I felt helpless. The last time we saw each other, she had become very thin and she said to me, ‘this is probably the last time I will see you. Make sure that you do something meaningful in life.’ After a month of our meeting, she passed away. When I heard the news, I felt lost, empty. A void had been created in my life. Then I started thinking very hard. I toyed with the idea of pursuing medicine. I reckoned that I could help thousands of people like my sister. That gave me a strong impetus to work hard, to get into medicine. I decided that I’ll do anything to become a doctor,” he reminisces.

A Chance Meeting

After becoming an eye doctor in 1985, he started working at Nepal Eye Hospital as a young ophthalmologist. “I had a lot of energy; I wanted to do something in Nepal,” he states.

Then he met Dr. Fred Hollows. “I met him by chance,” he says giving room to the possibility of divine intervention. Another doctor was supposed to pick up Dr. Hollows from the airport and Dr. Ruit just tagged along. “Since we were both eye doctors, he proposed that we meet at Hotel Summit to discuss matters over breakfast.” He confesses that he did not want to miss the chance of having breakfast in a nice hotel.

Dr. Hollows had come to Nepal as a WHO consultant. “We talked and during the process we reckoned that we liked each other a lot. He finished his WHO assignment in 15 days but because of his love for Nepal, the people and our friendship, he overstayed,” he recalls. What’s more, Hollows called his wife and kids to give him company for another 15 days. The group then went to the eastern part of Nepal and looked at some of the terrain and attended to some patients. By the end of his stay, their friendship had transformed into a stronger bond.

“He invited my wife and me to Australia and we spent a year with them. There we started making strategies from scratch as to how to set up things, how we can provide modern cataract surgery to such communities that exist in rural and faraway places in countries like Nepal. How we can cross the barrier of cost and quality and complexity. How can we break those and still produce good quality treatment?”…Dr. Ruit narrates the story of Dr. Hollows’ profound contribution in his professional accomplishments.

Family

According to Dr. Ruit, one of his life’s greatest achievements is his family. “Meeting my wife, Nanda, in whom I found a beautiful partner has bettered my life,” he shares. They belong to different communities. “It was not like today back then. Things were different more than 40 years ago,” he hints at the difficulties the couple had to endure on their way to holding on to their marriage. “Inter-community marriages were not easy. But we managed it. We have never regretted our decision,” he confides. His wife belongs to the Newar community. “We got married in 1987. We cherish our marriage. Family is very important. Seeing our children grow up - a son and two daughters - has been great,” he tells. “Beautiful children,” he adds.

The children are 29, 27 and 23 years old. The son is a doctor. The youngest one just passed medicine. “Not that I told them to pursue medicine as a career. But they chose to become doctors,” he said before I could ask if it was a reflection of his influence at home. “My other daughter helps me in my practice and also in the management of the Foundation,” he briefs.

Nepal Eye Program

Nepal Eye Program was established with the help of a group of NGO and television personalities as well as mountaineering and business entrepreneurs. It is a testament to the exemplary camaraderie shared among personalities representing multiple professions all working for a common cause. All these people from varied fields coming together and joining forces, it could not have been an easy feat. “It was not easy back then and I don’t think it is easy now either,” Dr. Ruit states. Basically, it was an attempt to have a good relations in the governing board. Individuals from varying backgrounds were picked for two fundamental objectives: a. for their expertise and backgrounds and b. for the impact they can make in the society.

Dr. Ruit shares names. “We had a chairman who was from a literary background - Jagdish Ghimire. We had a mountaineer – Shambhu Thapa. We still have Hari Bansha Acharya on the board. We have Suhrid Ghimire, Ravi KC who are businessmen; Govinda Pokhrel, who is a bureaucrat and Sanjay Thapa who is an engineer.”

He shares that a combination of people like these helps in making decisions for the institute in a more comprehensive approach. Dr. Ruit narrates his pursuit in getting them together, “It was in the early 90s that I pitched this idea. I showed them, on a piece of paper, what we can do and briefed them about the purpose that guided the inception of NEP - to deliver world class cataract service to the community and establish a world class eye care center. I told them that I want to establish an intraocular lens service facility. Naturally, one of them asked, ‘What do we have?’ I answered, ‘We’ve only $200 with us’ and he started laughing.” But it did not take much time for the people gathered to be swayed by the force of Dr. Ruit’s proposal. It was a tall order but they bought his idea. “They were of the opinion that it’s a crazy idea but saw the possibilities and the impact on human lives. We also discussed a little bit of what we can do and who the other allies could be.”

He elaborates, “So they were in it and saw it going so well and we continued to stick together. But basically, I think, being a technical field, it made sense that I created the match that they all complemented the team. I had a vision to bring together all these people from varied fields. You need management, financial expertise, public awareness… you need everything together to get it to work.”

It helped that Dr. Ruit was a recognised name by then. He says, “I had gathered a fair bit of credibility as a doctor and I was the most sought after eye doctor even then.”

Transforming Nepal’s Image

Tilganga Eye Hospital was established in 1994. The hospital is the implementing body of the Nepal Eye Program, a non-profit and non-government organisation. “Until now, for any capital investments - say we want to build a hospital outside, I need to raise funds for that. We take the help of certain business houses and individuals who give us money and we keep it very transparent,” he shares highlighting the importance of fundraising and running Tilganga.

Dr. Ruit’s eye hospital has now become synonymous with quality and credibility. The launch itself was a quiet event. “We were highly criticised for opening a hospital here. When you do a thing like that, a lot of people pull your leg. We had to stay underground for almost six months. After that, we opened,” recalls Dr. Ruit and talks about the little episodes that led to the authority that Tilganga has amassed today, “For the first time in Nepal, we showed surgery on live telecast. When people saw that, they realised the magnitude of the work we were doing.”

In technology and medical interventions, Nepal has a long way to go. It is a different story in eye care service though. Today, Dr. Ruit’s fame has travelled across continents. He is hailed for innovating a substantially cost-effective and simple eye surgical technique which earlier was complex and costly for the standard of those living in underdeveloped nations. His innovation made it possible for poor people to benefit from the state-of-the-art cataract surgery which was previously accessible and affordable only to the Western world or those who could afford it.

His service has benefitted people in Sikkim, Bhutan, Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), North Korea, Indonesia, Ethiopia and many other countries.

“We had to go out of Nepal so we thought the best way for us is to go close by. We went first to Sikkim and then to Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). We went wherever we could link up an access,” he briefs.

In TAR, they were given three places to do the surgery where they conducted 300 surgeries. The headquarters in mainland China was stunned as the first ever modern cataract surgery was done by Dr. Ruit and his team and what they had done in 10 days was something that was being achieved previously in 3-4 years.

“We had a really tough time in Indonesia,” he says about the initial days when they had to convince people that the invention and state-of-the-art surgery imported from Nepal was life changing. “We went to do surgery but I had the whole of ophthalmology fraternity there against me. I had a temporary license there. They said that they’d cancel my license and that it is their territory. They were not convinced that we could do such a big number of high quality surgeries. They were furious and they actually went to the government and complained that I be deported. We started by doing 30 cases every day for four days. But by the end of our trip, we had the ophthalmologists and other leaders coming to us requesting for more training,” he recounts.

“It was not easy. But now we get doctors from Indonesia, Myanmar, North Korea, China, India, Africa. They come because we have established a strong credibility. And they know the quality of eye care in Nepal. They know that we mean serious business,” he states.

Focus Drives Goals

The most important aspect of building an institution is having a good team. “I always focused on pushing the team forward. Without a good team, you cannot accomplish much. I would like to believe that I have been able to transmit the feeling of ownership in my team members. The success of NEP and Tilganga is because of the team,” he says. He reiterates his appreciation and gratitude towards his proficient team during the interview.

“Every year, we need to refocus because ophthalmology is a highly technology-driven branch and we need to be updated with new developments. The other thing we do is to draft a modern strategic management plan every 3-4 years and follow that. We also review the strategic management plan. That really helps us to reflect on what we did and what we want to do. The strategic management plan has to be owned by the executives. Until and unless it’s owned by the executives, there is no sense in having it in the first place. They are the ones who will be implementing the plan. They actually are part of developing it with the experts. We need experts to develop that but you need the feedback of all the executives. So, that’s really the key,” deliberates Dr Ruit on work efficiency.

He says, “I think in all institutions, even political institutions, you need to have a strategic management plan. If you have that, you can run it in a systematic process. In this era, you cannot run institutions efficiently, even hospitals, unless and until you have a business plan and a corporate structure. It is not like 10-15 years ago. It is important to have corporate structure.”

Dr. Ruit considers that the apolitical stand that the hospital has taken since its inception has been its greatest strength. “Though it was difficult embracing rigidness in matters concerning political interference, it has served us well,” he shares.

“If you look at the management of our hospitals, you have state-run hospital interventions and I have been very loud and clear in saying that they are not very efficient and run well and that there is no emphasis on quality. It depends on the leader and the leader may not be there all the time and because of inefficiency and corruption and many other elements in state-run interventions, private hospitals are mushrooming which is fine but the problem is that poor people cannot afford to go there. There is an economic barrier. What we’ve tried to hit is the in-between model which is more like a social entrepreneurship model with good quality. Quality is of essence but with a pricing tier. For people who can pay, allow them to pay more and for people who cannot pay, they can have the service for free. It is about cross-subsidy,” he explains.

“The reason the eye care center is successful is because of the model that we have created. Good, simple management and giving ownership to the people who run it. But the essence is quality and pricing tier. Making sure that the poor people who want to come in face no barrier,” he elaborates.

Forward Is The Only Way

“One thing we are trying to explore is the possibility of making intraocular lens manufacturing at a more professional and commercial level so that we can compete in the world market. That’s a reality for us to achieve,” he says.

Tilganga is already a WHO collaborating center. There are 10 such centers in the world and Tilganga is one of them. “We feel that is a prestigious thing for Nepal. We have a meeting going on upstairs; doctors from India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Thailand, Bangladesh, Pakistan are all here. They are talking about the next step in these countries. The idea is of collaboration. In simple terms it is about how to increase the impact. Nepal really plays a big role in global eye care development,” he says with pride.

“In eye care, a lot of us talk about trying to see how best we can take care of avoidable blindness which is blindness that is either preventable or curable and how we can take care of it. There are different ways. One such is establishing a community eye hospital such as the one we have in Hetauda. There are 2-3 doctors and about 30 staff doing about 6,000 surgeries in a year benefitting the grassroots level people, giving high quality service but still sustainable in meeting its operative cost, which is very important. Hopefully, this model will be replicable in other countries in Africa and Asia. We are trying to make it happen.”

-1767340083.jpg)