The 20th century saw a rapid growth of international trade and global economic integration. Economic globalisation has yielded significant results in the form of global economic growth and wealth creation. Economic integration has progressed in bilateral, regional and multilateral levels. Regional trading agreements have been assuming greater significance in recent decades. According to WTO Secretariat as of 1 July 2016, GATT/WTO had received notification of some 635 RTAs (counting goods, services and accessions separately). Of these, 423 were in force1. The RTAs acquired even greater importance in the 21st century as the Doha round of trade negotiations could not be completed in scheduled time, and countries relied on bilateral and regional trade agreements more than on multilateral ones in their pursuit of the benefits of globalisation. If one were to go through the media, one would realise that all economies of the world, barring pariah states like North Korea, are in some stage of negotiation of preferential or free trade agreements with other economies.

In terms of successful trade blocs, the European Union (prior to ‘Brexit’ vote) was hailed as the most successful one. The group which started as a vehicle of economic cooperation among six Western European nations in the field of coal and steel grew from strength to strength. The EU, in its journey of more than 50 years, has added newer territories as well as new policy areas. As of now it encompasses 28 nations in the whole of Europe and covers a wide spectrum of policy issues including fiscal, monetary, investment, standards and quality issues. The members of EU have made efforts to coordinate even their foreign policies, thus giving rise to the speculation of emergence of a political union in the form of a pan European Super State.

The EU is the largest single market. The 28 member nations of EU, with a little over 7% of the world population, generate more than one fifth of the Global GDP and compete with the US as the largest economy in terms of nominal GDP. The EU is often cited as the most successful regional trading bloc with other regional groupings taking cues from it for their integration initiatives.

The EU had sailed in rough waters on many occasions in the past, but it met a cyclone when the British electorate voted for ‘leave’ in the referendum on 23 June 2016 by a narrow margin. Although the formal exit of the UK from EU is yet to take place, the tremor of the ‘Brexit’ vote was felt over the entire world. Stock markets made a southward dip. So did the Euro and the Pound Sterling. The biggest losers were the companies which had huge European operations and had conveniently centred their European operations in the UK.

Even the staunchest advocates of the ‘Leave’ campaign agreed that there was the risk of the British economy going down at least in the near term. They saw such risk worth taking for continuing the British linkages with the world outside of Europe and their independence from the inspectors and regulators of Brussels. The opinions about the impact of the actual ‘Brexit’ (till now even the process of the exit has not been triggered) is divided to say the least. A lot will depend on the conditions or the terms of post exit British relationship with Europe. The British seem to be hoping for a free trade regime without the obligations of membership (like free movement of people, budgetary transfer, etc). But the continental Europeans have already been telling the Brits that there cannot be free movement of goods without free movement of people.

Naturally, euro enthusiasts who have been advocating for more openness and integration are more concerned with the ‘Brexit’ vote. They see the downturn in the global economy and even point to the possibility of another economic crisis. The euro sceptics point out that it may actually lead to a more natural and organic integration, as nations will concentrate more on cooperation at the global level.

When we consider the impact of ‘Brexit’ on our subcontinent we have to look from two aspects. On the one side we have to look at the impact on the national economies of the region. On the other side, we need to look at the effects on the process of regional integration itself in this subcontinent. Let us look at the impact on the economy first.

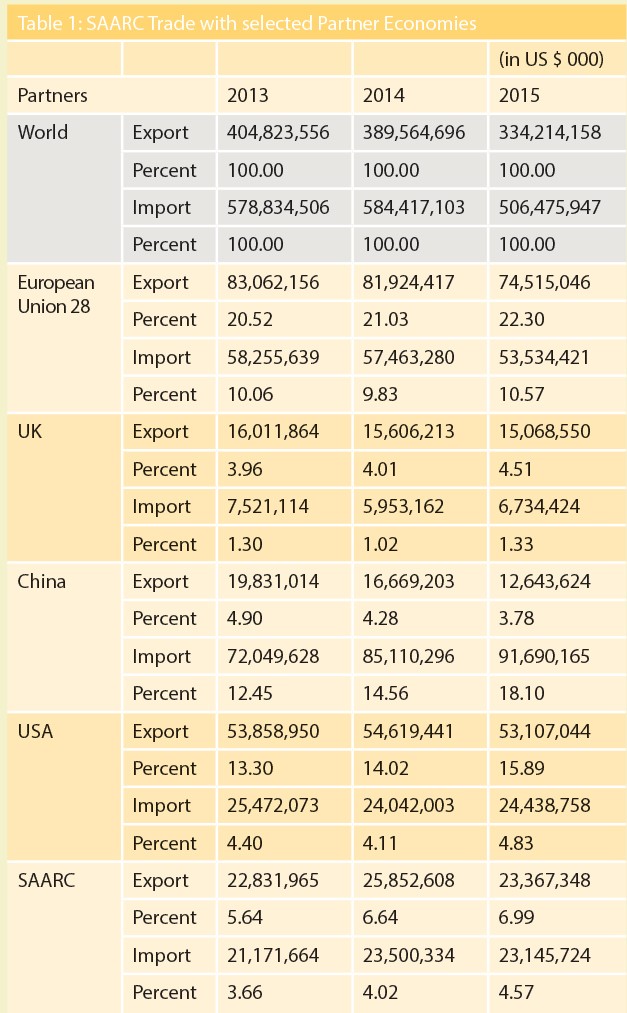

For SAARC economies, the European Union is the largest trading partner especially in export. More than 20% of export of SAARC countries goes to Europe. Only United States is somewhat comparable to the EU in terms of export market. So, anything that happens in EU is bound to have a major impact on SAARC trade. Among the EU countries, UK is a prominent market for the SAARC exports commanding over 20% of the total exports of the SAARC countries to the European Union.

Great Britain with her historical colonial linkage with South Asia and a large South Asian diaspora, has been the most important partner both in trade and investment in the South Asian countries. Most South Asian companies having their European operation are centred in the UK. On her own part, Britain was promoting herself to the outside world as a safe gateway to Europe.

With the exit of Britain from the EU, South Asians will have to find new European partners and maybe new places of business. In this age of global competition it is of course not an easy task to accomplish. It will also depend on how the EU itself will evolve. Already the right wing euro sceptics are flexing their muscles in continental Europe. Today, their target seems to be centred on immigration or foreigners coming to their land in large numbers. But if the economy were to suffer especially in larger economies like Germany and France, their anger may spill over to products and services coming from outside. In such a case, the life of suppliers from SAARC countries will become even more torturous.

The one logic or issue that was being repeated again and again during the campaign by the pro ‘leave’ campaigners was that Britain had to retrograde on her traditional linkages with the world outside of Europe as a result of her membership of EU. The pro-’Brexit’ campaigners kept on reiterating that Britain will be able to regain her past glory as a maritime power and pursue her own interests. If things were to happen that way, SAARC nations with their colonial linkages to Great Britain could enhance their economic links and cover whatever loss they would incur in their economic relationship with continental Europe. After all, the EU had traditionally made policy decisions that favoured either countries of their own neighbourhood or the former French colonies of Africa and the Caribbean. South Asian countries were accorded a lesser level of priority and importance.

Such prediction is based on the premise that Britain will not suffer significantly in economic terms, that London will continue to be the financial centre of Europe, and that continental Europe will not impose significant barriers on goods and businesses from Britain.

However, the one sure consequence of ‘Brexit’ is that the nation states of the world will now have one more party to negotiate with. Earlier one could enter into a single deal with 28 nations of Europe without dealing with every member of the group. Now, they will have to negotiate separately with UK. For nations with larger resources at their disposal, it may not be a big deal; but for smaller economies, it may prove to be costly and sometimes too taxing. With many negotiators across the table, it becomes difficult to come to an agreement.

The other thing that emerges clearly from this vote is that the period ahead will be tumultuous. Britain will be too busy negotiating with Europe on the terms of their new relationship. The scheduled expansion of the EU, especially the inclusion of Turkey looks grimmer than ever before. The EU politicians will be busy withstanding the onslaught of Euro sceptics, who have acquired significant inspiration from the ‘ leave’ win in the British referendum. In such turbulent times, marching ahead in the path of economic growth will be more challenging.

Apart from the economic impact on the relationship with the outside world in general and Europe in particular, the impact will also be felt in the SAARC process itself. The SAARC has been quite slow in the regional integration process. The trade and investment flow within the SAARC is way below expectations. The geographical proximity and the cultural affinity have not resulted in economic imminence.

Although SAARC nations have made significant strides in economic progress in recent years, the performance is uneven. The coming into force, the agreement on a Free-Trade Area (FTA) has not resulted in significant growth of intra-regional trade.

With ‘Brexit’ the support base for regional integration gets a beating. Sceptics are much more emboldened. No more can we say that the historical competitors like Britain and France and enemies of the two great wars, Britain and Germany are successfully collaborating in the EU. Although no one can take away the fact that the British economy is likely to be closely integrated with her European neighbours.

The ‘Brexit’ has proved that for successful integration, it is not sufficient that an econometric model yields significant positive outcomes from it, but the people have to feel it in real terms. When Britain was trying to join the European Economic Community, the predecessor of the EU, in the 60s, she was a laggard and the French President of that time Charles De Gaulle had vetoed the British entry declaring “l’Angliterre, ce n’est plus grand chose” (England is not much anymore). At that time, Britain had lost her colonies and her economy was stagnating. This was almost an insult to the British pride. She could only become a member of the EEC when De Gaulle resigned from the French presidency.

In 2016, when Britain has decided for an exit from the EU, she has one of most successful if not the most successful economies of the bloc. In the campaign, the traditional blue colour workers (predominantly white males) were supporting the leave campaign, where as the more cosmopolitan white colour professionals were by and large for the ‘remain’ side. This proves the need for the ordinary people to realise that the regional bloc is doing something good to them and is in their interest.

The integration process will always have winners and losers. The gains are somewhat visible only in the long term and have to be acquired with strategic efforts; whereas, the losses are immediate and the losers will feel it directly. It is in human nature to think that the gains are due to one’s own effort, while the losses are due to ‘others’. So in order to generate sufficient support for regional integration, not only the economists and intellectuals, but also the ordinary folks need to be convinced about the net positive gain. Proper communication from the government about the gains and pains of the integration is needed. Are the SAARC governments and businesses listening?