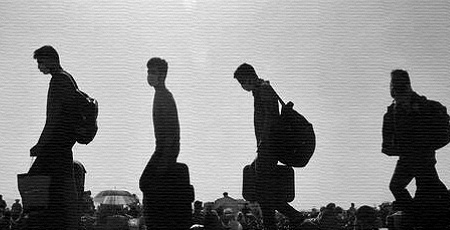

Until the middle of March 2000, government and people in Nepal thought that Covid 19 pandemic is tractable. Segments of tourism industry that relied mostly on foreign tourists had started to feel the coming on of a dreadful period. Other contributors to the economy were generally unaffected. Government thought that it can be contained with conventional wisdom. People were asked for mass lighting of diyas hoping that with this collective act, hitherto unknown virus will not dare to invade. In neighbouring India, people obediently lit diyas, banged pots and pans in unison, and honoured the government-announced people’s curfew. These didn’t work, the virus tricked the tricksters. Then came a hastily announced lockdown. The border between India and Nepal was closed abruptly without considering that there might be people in the middle of their journey returning home. Normally around the end of April every year, thousands of Nepali seasonal workers return from short-term work in the different Indian states. As businesses closed, construction activities stopped, many Nepalis found themselves out of job. They defied the lockdown and walked hundreds of miles to return home little earlier than they normally did in the past years. They arrived at different border points in western Nepal bordering Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh of India only to find that Nepali authorities would not let them in. For days, hundreds of groups of people camped near the border at different checkpoints urging authorities to show compassion to people who brought much needed remittance to their home country. Some even risked their lives to cross the mighty Mahakali river swimming in the night to enter homeland.

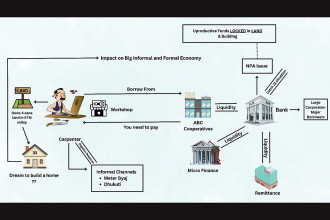

Ultimately, the federal government -responsible for border control - relented as local municipalities and provincial governments reported that the situation in makeshift camps on the other side of the border holding returnees was getting worse. There was some relief. Several returnees spoke to media about their plight. They said they would find work in their own place and not go for short-term jobs in neighbouring country. The provincial and municipal government promised that there would be jobs for people. Tall promises was made by the federal government through the new budget announced for fiscal 2021 that new job creation programs will have substantially higher allocation and will target those who are forced to leave native places just for short-term jobs. The promises failed; people preferred “making a living” than “saving lives” For a few months after returnees were allowed in, government officials were hopeful that there will be renewed impetus on agriculture and micro-enterprises as younger people will remain in their villages, they will try innovation in subsistence agriculture, start micro-industries in the villages and economy will gain more than what the meager remittance was giving. Politicians claimed that the Covid crisis also came with good opportunity. However, just a few months later, the scenes at the border checkpoints was more than reversed. Beginning from the third week of August, even when tough lockdowns in Nepal were not relaxed and the spike of Covid 19 cases in India were at its peak, thousands of people started queuing at several border checkpoints for entry into India, obviously for jobs. Many of them had invitation from previous employers, from apple orchard owners in Himachal Pradesh, etc.

In normal years, this was not the time for Nepali seasonal worker exodus into India. People migrated mostly after all the autumn festivities and when the summer crop harvest was over. The freezing winter and lack of jobs in their locality have been major reasons for people in the western mountain region of Nepal to migrate to India for seasonal jobs; it has remained a long tradition. Between August and December 2020, it was estimated that over 20,000 people crossed the border every day for short-term jobs on the other side. Almost invariably, everyone asked at the checkpoints reported that “making a living” is important than “life” itself, therefore they were willing to take the risk even knowing that Covid 19 cases in India had peaked. Most municipalities in the region from where people left for India didn’t even try to assess why their citizens were moving out, let alone implement employment generation programs that could hold people in their homeland. Some influential provincial and municipal authorities interviewed claimed that people were exercising their freedom and they were leaving on their volition. Federal government’s plethora of programs for employment generation did not take off due to institutional weaknesses. As a result, a better change that was just about to come, simply vanished.