The tragedy of the commons is at the heart of many of our environmental issues, revealing the power of incentives.

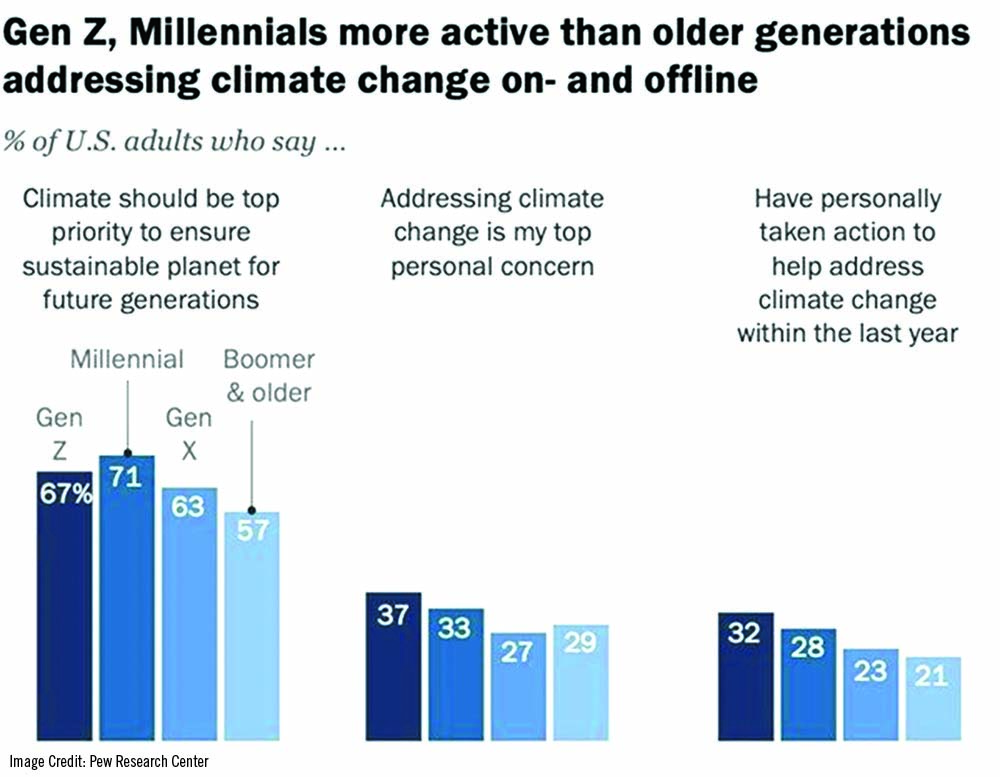

Polling has consistently shown that millennials and Gen Z rank climate and environmental issues among their top political concerns. The next generation is eco-minded, as demonstrated by youth marches, school strikes, and trendy Instagram graphics. Interestingly, polling also shows that younger generations are keen on big government, top-down legislation, and even socialism, with 70% saying they would vote for a socialist. Millennial and Gen Z voting habits indicate that despite their deep environmental concerns, they remain unaware of how best to care for our environment, often advocating policies and approaches that won’t achieve their desired outcome – a healthy and thriving planet. Environmentalists and left-of-centre politicians whose interest in environmental issues is rhetorical often prioritise preservation, while those who work hands-on with natural resources prefer conservation. To understand the different approaches, imagine an outdoorsman who has purchased land hoping to spend time with nature. A preservationist would contend that the outdoorsman may access his land and enjoy its inherent natural beauty but any tampering with its ecosystem would disrupt its intrinsic value; therefore, the land must be left alone.

A conservationist, by contrast, would encourage the outdoorsman to manage the land actively. He might plant a grove of native fruit trees or hunt to ensure local fauna does not overpopulate. Conservation efforts require the outdoorsman to participate in and improve his environment, for the long-term benefit of both.

Should the outdoorsman choose conservation, his responsible management will increase the value of the land – a sure benefit to a property owner. This incentive holds the outdoorsman accountable, acting as a check. Clearly defined property rights discourage the misuse or mismanagement of resources.

Illustrating this dynamic is Garret Hardin’s classic 1968 article “The Tragedy of the Commons,” in which he describes a herdsman facing a choice over the use of a common pasture.

The herdsman, noting that the land was open to all, bore no responsibility for the upkeep of the pasture. Upon realising this, he concludes that adding an animal to his herd would increase his profit at no added cost to himself. His fellow herdsmen each arrive at the same conclusion, and with each acting in his own interest, the pasture is soon over-grazed, resulting in underdeveloped livestock and barren land, at great cost to all.

A preservationist would contend that the outdoorsman may access his land and enjoy its inherent natural beauty but any tampering with its ecosystem would disrupt its intrinsic value; therefore, the land must be left alone.

A conservationist, by contrast, would encourage the outdoorsman to manage the land actively. He might plant a grove of native fruit trees or hunt to ensure local fauna does not overpopulate. Conservation efforts require the outdoorsman to participate in and improve his environment, for the long-term benefit of both.

Should the outdoorsman choose conservation, his responsible management will increase the value of the land – a sure benefit to a property owner. This incentive holds the outdoorsman accountable, acting as a check. Clearly defined property rights discourage the misuse or mismanagement of resources.

Illustrating this dynamic is Garret Hardin’s classic 1968 article “The Tragedy of the Commons,” in which he describes a herdsman facing a choice over the use of a common pasture.

The herdsman, noting that the land was open to all, bore no responsibility for the upkeep of the pasture. Upon realising this, he concludes that adding an animal to his herd would increase his profit at no added cost to himself. His fellow herdsmen each arrive at the same conclusion, and with each acting in his own interest, the pasture is soon over-grazed, resulting in underdeveloped livestock and barren land, at great cost to all.

“Therein is the tragedy,” Hardin concludes. “Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit—in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.” Hardin’s story demonstrates that effective resource management relies on good incentives, best derived from ownership. Property owners are incentivised to use resources sustainably because failing to do so would result in their own misfortune. In Hardin’s parable, environmental degradation occurs because no herdsman owns the pasture, so, no one has the incentive to ensure it is used sustainably. Young people are right to be concerned by environmental challenges, including climate change, ocean plastic pollution, and the National Park deferred maintenance backlog. What these challenges have in common, however, is that no entity is made to feel the consequences of their neglect. The tragedy of the commons demonstrates why, for all their concern, activists should not rely on the federal government to adequately address environmental problems. The strongest incentive to protect property is ownership, where individuals must face the consequences (positive and negative) of their actions. Simply explained by philosopher Aristotle, “people pay most attention to what is their own; they care less for what is common.” This is why environmental approaches prioritising preservation and common property pale in comparison to the results achieved through private conservation. As young people around the world continue to advocate for a healthy planet, they would do well to embrace clearly defined property rights and conservation practices. By encouraging interaction with our environment, we will not only achieve better environmental outcomes, but also foster a culture rooted in a love for natural places. Source: fee.org READ ALSO:"Millennial and Gen Z voting habits indicate that despite their deep environmental concerns, they remain unaware of how best to care for our environment, often advocating policies and approaches that won’t achieve their desired outcome – a healthy and thriving planet."

Published Date: March 28, 2022, 12:00 am

Post Comment

E-Magazine

RELATED Economics